BALANCING OLD AND NEW ON ALEXANDRIA’S HISTORIC WATERFRONT

A new master plan for Old Town, the historic center of Alexandria, Virginia, just a few miles from Washington, D.C. which has been in the works for more than five years, is now well underway, as the city opens bidding on the plan’s flood mitigation improvements. The plan will transform one of the last “undeveloped” major urban waterfronts in the D.C. area. The $120 million project, designed by landscape architecture firm OLIN, will add 5.5 acres of public open space; develop a new signature plaza at the foot of King Street, the main thoroughfare through Old town; expand the marina; create walkable connections for the length of the waterfront; and incorporate flood mitigation measures. Three new mixed-use developments have also been proposed along the waterfront, including a plan to transform Robinson Terminal North. These plans come for approval by the local planning commission and city council in September.

Phase one of the project, which will not be completed until at least 2026, will focus on core utility, roadway, and other infrastructure construction required to support the subsequent street-level improvements, followed by attention to the flood mitigation elements, one of the more controversial elements of the project, according to The Alexandria Times. At a recent talk at the National Building Museum, “Alexandria’s New Front Door: Implementing the Waterfront Plan,” it became clear that the discussion on flood mitigation illuminates the key challenge in re-envisioning Alexandria’s waterfront: how to maintain the character of one of the U.S.’s most historic cities while protecting this architectural treasure-chest from the threat of increased flooding.

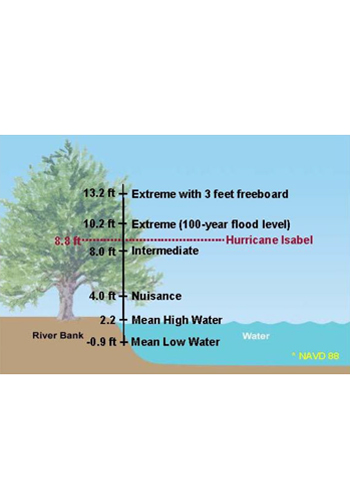

Old Town Alexandria was hit hard during Hurricane Isabel in 2003. According to The Washington Post, flooding from the Potomac River swamped the historic Torpedo Factory and many areas around King Street. Along Alexandria’s waterfront, streets were navigated by canoe and kayak, as water levels reached nearly 9 feet above sea level. More recent storms, such as Hurricane Irene in 2011, were also devastating. Long-term, Alexandria’s Potomac waterfront will experience sea level rises of more than 2.3 to 5.2 feet by 2100 — according to the Waterfront Small Area Plan — and certain areas of the city now flood at least once a month, so OLIN made flood mitigation a high priority in the master plan.

Based on a 2010 flood mitigation study commissioned by the Alexandria city government, OLIN proposed a comprehensive plan that balances mitigation, cost, and maintaining views. The waterfront plan will protect against nuisance flooding at 6 feet higher than sea level through drainage improvements, a combined sea wall and pedestrian walkway, and the use of green infrastructure techniques such as swales and rain gardens. Not only will this protect Old Town against the majority of flooding, this level of protection was found to be the most cost-effective and least visually intrusive for the majority of flooding events, according to a 107-slide presentation by OLIN.

However, the historic character of the city may still be at risk during major storms. “The level was set at 6 feet so it would not destroy the character of the viewshed or the city’s historic character, but this flood mitigation will be overtopped eventually,” said Tony Gammon, acting deputy director of the department of project implementation for Alexandria, at the National Building Museum. “It won’t be a surprise to us.”

Other elements of the waterfront project, which were decided based on extensive community input, strike a balance between preserving character and improving function quite well. According to the small area plan, “throughout the planning process, Alexandrians asked for more ‘things to do’ on the waterfront.” Once a working waterfront bustling with commercial activity, Old Town’s current attractions are now primarily located in-land. The new plan aims to bring a high level of activity back to the waterfront in a new form. A public boardwalk along the water’s edge will improve access to the river, while new public spaces, including a large public park called Fitzgerald Square, will bring people to parts of Old Town that were formerly industry-dominated. Old buildings will be memorialized, views to the river from King Street will be opened up, and three derelict sites will get new mixed-use development.

According to Robert M. Kerns, development division chief for Alexandria, who spoke on the National Building Museum panel, the crowning achievement of the project has been its ability “to balance new development with the city’s historic patterns.” Preserving historic character was not only a consideration for the flood mitigation strategies, but also for the city’s new promenades and public spaces. For example, the proposed Prince Street promenade, which will end at riverfront, will have a series of formal gardens that complement the scale of the surrounding structures. “Ensuring an historic scale was important to city identity, as was following the pattern of existing buildings,” Kerns said about the proposed promenade.

But do the character-conscious flood mitigation strategies go far enough to protect Old Town from the next super storm? While Alexandria is unique due to historic character, the careful approach to flood mitigation provides a contrast to cities like New York City and Boston, which have recently held design competitions that have yielded ambitious waterfront resiliency plans in the wake of Hurricane Sandy. The projects that have come out of Living with Water in Boston and Rebuild by Design in NYC will be designed to withstand catastrophic storm events, far more than a 6 foot nuisance flood. While New York and Boston are bigger cities, and arguably at greater risk from sea level rise than Old Town, the effort in Old Town raises questions about the depth of resilience being planned and designed.

After years of debate over the Old Town waterfront, there is now some consensus on how to upgrade this historic place with new parks, better access to the waterfront, and improved flood mitigation. However, the project, which will be in the works for the next decade, ultimately proves just how much “new” residents of one of the country’s oldest cities are willing to accept. Continued flooding may be the price.

Follow Us!