BIOMIMICRY TOOLS TO INSPIRE DESIGNERS

“Biomimicry is about learning from nature to inspire design solutions for human problems,” said Gretchen Hooker with the Biomimicry Institute at SXSW Eco in Austin, Texas. To enable the spread of these exciting solutions, Hooker, along with Cas Smith, Terrapin Bright Green, and Marjan Eggermont, Zygote Quarterly (ZQ), gave a tour of some of the best resources available for designers and engineers of all stripes:

AskNature.org

Hooker walked us through AskNature.org, a web site with thousands of biomimicry strategies, set up by the Biomimicry Institute. The site organizes biological information by function. “Everything nature does fits into a function. And these functions enable us to connect biology to design.”

AskNature first organizes strategies into broad functions and then zooms down into the specific. For example, a user could click on the broad function group, “Get / Store / Distribute Resources,” and then navigate to “Capture, Absorb, and Filter,” and then select “Liquids,” which has 52 strategies. One such strategy describes how the nasal surfaces of camels help these desert animals retain water. Another looks at how the horny devil, a desert lizard, uses its grooves to gather water from the atmosphere. There are just as many plant-derived strategies as there are animal ones. One such strategy looks at how the arrangement of epiphytes’ leaves aids in water collection (see image above).

All of these strategies are written in a non-technical way for a general audience. Hooker said they have selected the most “salient examples, backed with credible research citations.” Users can then go explore the citations and pull out excerpts.

Tapping into Nature

Terrapin Bright Green, a sustainable design consultancy, produced Tapping into Nature, a comprehensive online report covering the world of biomimetic design, which includes an amazing interactive graph. Cas Smith, a biological engineer, explained that the report and graph seek to “uncover the landscape of biomimetic innovation, with a roadmap that shows designs and their their stage of development: concept, prototype, development, or in the marketplace.”

“Biomimetic design is now found in almost all industries — power generation, electronics, buildings.” But to make things easier, Terrapin organizes the design strategies into the following sections: water, materials, energy conservation and storage, optics & photonics, thermal regulation, fluid dynamics, data & computing, and systems.

Using the graph, Smith picked out one story: the firm Blue Planet, which is mimicking the bio-mineralization processes of coral reefs, which pull carbon dioxide out of the water to create their unique structures, to create a new type of carbon-based building material. The firm is also creating pigments and powders. Another highlight: early exploration of termite humidity damping devices. Termites create massive mounds, mostly underground, which are equal in scale to a skyscraper for us. Within the mound, temperature and humidity levels are tightly controlled so they can grow the fungi they live on. In some of the mound’s subterranean rooms and chambers are bright yellow objects about the size of a fist. These structures are termite-created sponges that actually pull water from the air. Smith related to this to HVAC systems in human buildings, and how new systems could be created to remove humidity with giant sponges in a more energy efficient way.

Smith said the process of creating biomimetic innovations is similar to that of a typical innovation development process. “There’s just the added layer up front.” While there are risks in any process, biomimetic designs, he argued, will be the source of “breakthrough products for solving our problems.” If the designers and engineers creating these new products and processes follow nature, “they can embed sustainability throughout.”

Zygote Quarterly

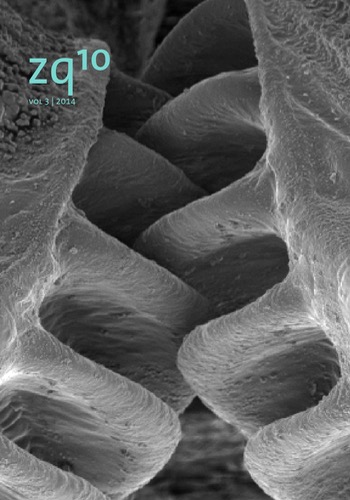

Marjan Eggermont, an instructor at the Schulich school of engineering at the University of Calgary, is the co-editor of Zygote Quarterly (ZQ), which biomimicry pioneer Janine Benyus called as “ecstatic as nature.” The magazine uses compelling imagery, interviews, and case studies to provide a historical record of the growing biomimetic design movement.

One issue explored Issus, a backyard bug, that has gears in its nymphal form. “We thought we invented gears but it turns out we were wrong. Nature already got there first.”

The gears, which Eggermont’s engineer husband modeled and then 3-D printed, were passed around so we could check them out. According to Eggermont, the gears are “remarkably self aligning, backlash free, with a one-directional timing mechanism that sweeps through a subtle 3D path.” They could potentially be applied to our world as “evolved mechanisms, ad hoc hinges, for seldom-used orchestrated movements — precise movements.” Eggermont thinks they could one day be used in space crafts.

But thinking more broadly, Eggermont sees the magazine as an educational tool. In the future, she wants each case study in the magazine to have a link to a 3D file that can be downloaded and printed. Real models could then be passed around in classrooms or design firms for inspiration.

Benyus, who was also in the session, went even further, calling on fans of biomimetic design to go to natural history museums, scan the natural forms and create a worldwide library of digital files that could be widely accessible as design models. “We can have a scan jam.”

Follow Us!