Don’t compare the US surviving 1968 to 2018. It’s an earthquake now

The Guardian

It is tempting to find reassurance in the comparison: America survived the turmoil, division and bloodshed of 1968. I find no basis for such solace

During the turbulent year in 1968, when I achieved Jewish manhood as a barmitzvah, I took on a more concrete form of maturity with a job delivering newspapers. Making the rounds of my New Jersey hometown, tossing copies of the Daily Home News onto 70-odd porches, I almost literally trafficked in the tragedies captured in each banner headline.

My mother was doing the favor of driving me along my route on the rainy April night when we heard the radio bulletin of Martin Luther King’s assassination. On the June afternoon after Robert F Kennedy was slain, one of my customers asked me how the paper could even be published. Several days later, Kennedy’s funeral train rolled along the Penn Central tracks right through my hometown of Highland Park.

In the last week of the year, the Daily Home News treated all of its delivery boys (and they were only boys back then) to a special screening of the Beatles’ animated film Yellow Submarine. I still remember feeling both delighted and destroyed by the simple, tuneful, colorful way the Fab Four triumphed over the evil Blue Meanies. At the film’s end, after all, the real Beatles came on screen to warn that there would be “newer, bluer meanies” in the days ahead.

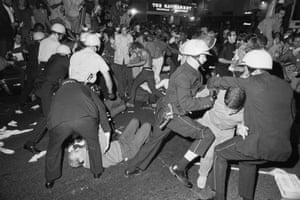

At the resonant remove of 50 years, historians and commentators and civilian graybeards like myself have gazed back at the shocks and strains of America in 1968 – Vietnam escalation, growing anti-war protests, assassinations of idealistic heroes, race riots, demagogic politicking – to help us comprehend the awfulness of the disunited states of the Trump era. My own children, in their mid-20s, have asked me more than once how 1968 compares to 2018.

As both parent and citizen, it is tempting to find a reassuring moral in that comparative story: America survived the turmoil and division and bloodshed of 1968, and it will do the same with the emergent authoritarianism of 2018. Having lived through both years, however, I find no basis for such solace.

For very palpable reasons, 2018 presents a more dire situation. Even though the Vietnam war appeared to be the primary polarizer of Americans in 1968, Gallup polls taken throughout the year show that national opinion was swinging decisively against the war, by a 17% margin heading into the presidential election.

Then president Lyndon B Johnson, who had overseen the misbegotten expansion of American involvement, was by the fall of 1968 seeking peace talks. And on domestic policy, Johnson had put through the most important civil rights laws since emancipation and the greatest expansion of the social safety net since the New Deal. His problem, paradoxically, was that he raised expectations so high, so fast, that when reality could not keep pace, especially in race relations, black anger and white backlash ensued.

Two of the three presidential candidates in 1968, Richard Nixon on the Republican line and the populist independent George Wallace, played to race and class resentments, Wallace overtly and Nixon by coded euphemisms. As president, Nixon ultimately put journalists and news organizations on his so-called “enemies list” and dispatched the vice-president, Spiro Agnew, to denounce the mainstream media as “nattering nabobs of negativism”.

So, the historical picture is grim. But Wallace never won office beyond the governorship of Alabama. Later in his life, having been paralyzed by an assassin’s bullet, he renounced his previous bigotry and personally apologized to veterans of the civil rights movement.

As we have seen in the last week, such heartfelt contrition will never come from Trump. His sole impulse, in the wake of the bombs sent to more than a dozen media and political figures he had repeatedly reviled, was to mouth some scripted words about unity and then get back to pouring gasoline on the fire he set in the first place.

While Nixon may have wanted to delegitimize the media as “fake news”, the effort could not succeed for both commercial and technological reasons. Admittedly, the ballyhooed “good old days” of American journalism circa 1968 had plenty of downside; the typical newsroom was monochromatically white, male and straight, and self-satisfied in its own narrowness.

Yet the more constrained media market also meant that there was a basic, agreed-upon set of facts in American public discourse. With just three network evening newscasts, with massively popular general-interest magazines like Life and the Saturday Review, with a newspaper of record likethe New York Times that influenced the entire print industry right down to local papers like the Daily Home News, the essential saga of Vietnam, of race, of the presidential campaign was not susceptible to presidential fabrication.

Time magazine might lean slightly right of center, its competitor Newsweek position itself faintly to the left; ABC seemed somewhat conservative in its national newscast, as CBS inclined toward liberalism. But a basic set of public truths, while subject to varying ideological interpretations, could not be plausibly denied by any responsible person.

For that matter, Nixon and his Democratic opponent, Hubert Humphrey, both espoused policies that largely subscribed to the post-second world war consensus: a New Deal-style welfare state at home, containment of communism abroad.

Nothing in 1968, despite all its traumas, bears a likeness to Donald Trump, his administration and his high-profile enablers with their rampant and shameless mendacity, myriad bigotries, explicit incitement to violence against journalists, racial minorities and political foes. Technological advances and market forces have allowed these toxins to spill profitably into rightwing pseudo-journalism and the sewers of social media.

It is commonplace but utterly wrong to think the fault for 2018’s poisonous climate falls equally on Democrat and Republican, social-justice progressive and Trumpian conservative. As studies have shown, one side of the divide still gets its information largely from trustworthy, curated, fact-based sources; the other hears only the echo chamber of extremism – and inspires its most unhinged acolytes to bomb and shoot accordingly.

The tremors of America in 1968, destabilizing as they were, rumbled from below. The full-scale earthquake of 2018 has been activated from above, from the highest office in the land.

- Samuel G Freedman, an occasional contributor to the Guardian, is a journalism professor at Columbia University and the author of eight books

Since you’re here …

… we have a small favour to ask. Three years ago, we set out to make The Guardian sustainable by deepening our relationship with our readers. The revenues provided by our print newspaper had diminished. The same technologies that connected us with a global audience also shifted advertising revenues away from news publishers. We decided to seek an approach that would allow us to keep our journalism open and accessible to everyone, regardless of where they live or what they can afford.

And now for the good news. Thanks to all the readers who have supported our independent, investigative journalism through contributions, membership or subscriptions, we are overcoming the perilous financial situation we faced. Three years ago we had 200,000 supporters; today we have been supported by over 900,000 individuals from around the world. We stand a fighting chance and our future is starting to look brighter. But we have to maintain and build on that level of support for every year to come.

Sustained support from our readers enables us to continue pursuing difficult stories in challenging times of political upheaval, when factual reporting has never been more critical. The Guardian is editorially independent – our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important because it enables us to give a voice to the voiceless, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. Readers’ support means we can continue bringing The Guardian’s independent journalism to the world.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

Follow Us!