HOW ONE COUNTY TOOK ON ATLANTIC COAST PIPELINE — AND THE TRUE COST OF NATURAL GAS

By Brad Horn THE WASHINGTON POST

Battling a pipeline

View Photos

In Virginia, one woman’s fight to save her land

Glass Hollow Road is a stretch of black asphalt in Virginia’s rural Nelson County, just west of Charlottesville. Ringed by lush green mountains, it runs for a mile or two before being swallowed by the forest. It’s lined with an occasional house, an occasional cow, and nothing is optional about waving to an oncoming driver.

A short way down the road is a little white, single-story house and a not-so-little white barn, along with a dozen rusty vehicles slowly becoming one with the earth.

For this house, there have been two pivotal moments in recent memory.

The first occurred in December 1977, when a 19-year-old Virginia native named Heidi Cochran first laid eyes on the home and its four acres. The view was so lovely she didn’t even go inside before telling the real estate agent they’d take it. She and her husband then got to work on a back-to-the-land homestead executed with countrified flair.

The second pivotal moment occurred 36 years, six months, two husbands (and two separations), four children, 29 horses, 19 dogs and seven cats later on a sunny afternoon in May 2014, when Cochran walked down the long gravel driveway to her mailbox.

Cochran, 55, had become a self-employed electrical contractor. Her skin was now chapped from the sun, her hands calloused, but her braided hair still hung to her waist. She called herself “the old fat lady back in the hollow.”

Over the years she had purchased two adjoining plots, bringing her slice of paradise to 16 acres, enough to hope one of her four children might one day build a home next door. She didn’t know it yet, but that fantasy was in great peril.

In the mailbox she found a letter from Dominion Energy. She read something about a natural gas pipeline, then tossed it aside. What do I need with natural gas? she thought. She heated with a wood stove. But Cochran misunderstood: Dominion wasn’t offering her anything. It wanted something from her.

Volunteers paint “No Pipeline” on Heidi Cochran’s barn to show her opposition. (Jay Westcott/For The Washington Post)

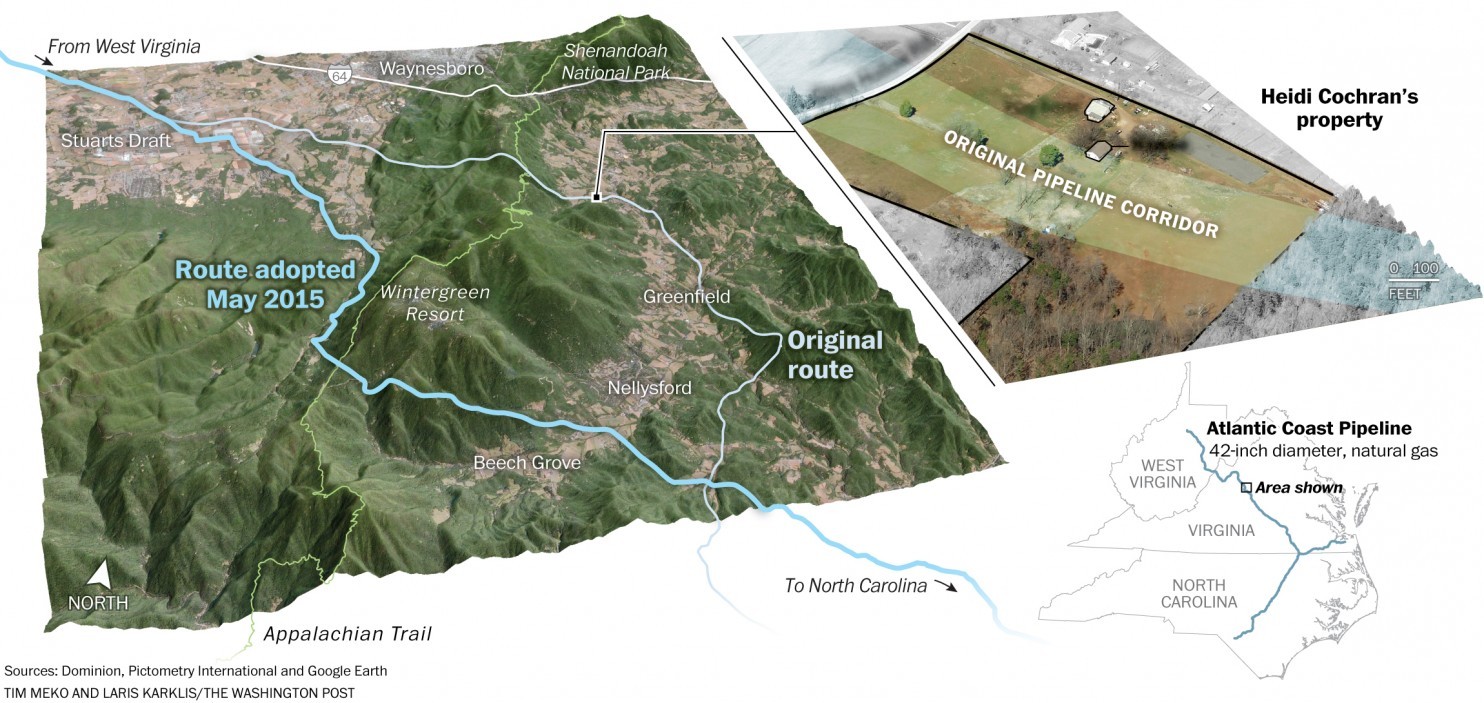

If it made it through the arduous approval process, Dominion’s proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline — 560 miles long from the hills of Harrison County, W.Va., to the red clay of Robeson County, N.C. — would carry natural gas to southeastern power plants that are phasing out coal. Dominion, Duke Energy, Piedmont Natural Gas and AGL Resources are partners in the project. Construction would begin in late 2016, the operation coming online two years later. Richmond-based Dominion would construct it.

At 42 inches in diameter, the pipeline would be part of a new generation of American mega-pipelines built to transport our dizzying windfall of natural gas. At full pressure, it would move 1.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day. It would be almost as large as American pipelines come.

There are four large natural gas pipelines underway in the Eastern United States, what some energy experts have described as a “natural gas race” to bring gas to the East Coast. Energy companies are being incentivized by Environmental Protection Agency regulations championed by the Obama administration called the Clean Power Plan . The plan would essentially regulate coal-fired power plants out of existence, replacing them with gas-powered facilities. The goal is a dramatic overhaul of America’s energy grid and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

The pipeline’s champions say it will significantly reduce carbon emissions while creating jobs along its route. Detractors say the $5 billion project will lead to more methane emissions (themselves a highly potent greenhouse gas) from the controversial natural gas drilling technique known as fracking, violate private property rights and disrupt fragile ecosystems when it passes through some of the more intact wilderness of the southern Appalachians.

What isn’t argued is whether the United States needs a replacement for coal. Coal-fired power plants generate 33 percent of the nation’s electricity but 71 percent of our carbon emissions, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). This gives coal the distinction of being the nation’s single largest contributor to climate change.

“One out of every 15 tons of carbon dioxide emissions that goes into the atmosphere anywhere in the globe is from the United States power sector,” says Susan Tierney, a former assistant secretary for policy at the U.S. Department of Energy. “[That’s from] us plugging in our iPhone chargers. We’ve got to do that more cleanly, got to do it much more efficiently.”

Opponents wondered: Why not simply convert to a system powered by renewables?

Renewables can’t meet demand, says Tierney, now an adviser at Analysis Group, a consulting firm. To replace coal with wind, solar and geothermal infrastructure (which supply just 5.7 percent of the nation’s electricity, according to the EIA), “you have to put in a whole lot more resources, making it much more expensive to replace a coal plant.” One of her biggest concerns, Tierney says, is that “opposition to a natural gas plant will mean coal plants stick around longer.”

“Climate change is occurring,” she says, and decommissioning coal plants can’t wait.

Heidi Cochran’s best guess, based on Dominion’s route maps, was that the pipeline would come 100 feet behind her house, running through a field, then making an abrupt right turn before her pond, traversing instead through a patch of large locust trees to Glass Hollow Road.

According to Dominion spokesman Aaron Ruby, roughly 2,700 total landowners were making calculations like those, pondering how the pipeline would affect their property. They were told the pipeline required a permanent clearing, a 75-foot-wide “right of way” on which nothing but small plants could grow. According to Dominion’s literature, the right of way could still be used for most agricultural endeavors such as planting crops and grazing livestock, but landowners couldn’t grow trees or build houses on the land, and new road constuction would be limited.

The restrictions were devastating for Cochran: “There will be no building sites left,” she said. And “it’s really hard to even hope my children would come back and live on a piece of property that they will die in if there’s ever an explosion. I’ll protect them with everything I’ve got.”

Coming from Cochran, “everything I’ve got” could feel daunting. She had become an electrician at 22 because a male electrician told her it wasn’t a job a woman could do. Once, she fell from a ladder and impaled her jugular vein with a screwdriver. Doctors told her she should have died; today the scar runs almost from ear to ear.

She was raised on Virginia’s Fort Monroe, then an Army base at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. At 17, Cochran ran away for the West Coast with her soon-to-be-husband, a man one year her senior named Doug Griffin. One day she told her parents she was taking the dog for a walk, then she and Griffin hit the road. She brought only two possessions: her dog and her riding saddle. Why take the saddle if she wasn’t taking the horse? “It was a really nice saddle,” she says.

After extended travels in California and New Mexico, and a brief residence in Dallas (where Cochran gave birth to their daughter Sage at home), the couple decided to move closer to family. Soon they were looking at a Nelson County property on a road with a curious name: Glass Hollow.

Cochran divorced Griffin in the mid-’80s, then in 1990 married a friend of her ex-husband’s named Wiley Cochran. Wiley brought another daughter into the family, Erica. In 1991 they had Emily, and in 1997 a son, Mickey. Despite having four children underfoot, says Cochran, they were known for having outrageous houseguests and massive bonfires, and for a proclivity to shoot clay pigeons packed with gunpowder.

They bought a third contiguous plot in the area known as Glass Hollow, which meant the property now had a large field, two horse pastures, a small fishing pond and half a hill covered in hardwoods.

Cochran says she and Wiley separated in 2010, but they remain legally married and share ownership of a plot Dominion wanted for the pipeline.

Pipeline: Crossing Location

Embed Share

Play Video0:44

(The Washington Post)

At the beginning of 2015, Cochran was keeping up with the pipeline and was moonlighting as a waitress after her day job while also keeping tabs on her family. Mickey, a 17-year-old high school senior, lived at home; Emily, 23, lived at home and worked as a fledgling wealth management analyst in nearby Charlottesville; Sage, 38, was a mother of two in Tennessee; and Erica, 35, lived three hours to the east in Gloucester, Va., and often spent weekends in Glass Hollow with her toddler son.

Cochran was down to sleeping just two or three hours a night, the other hours occupied by worry. She had lost the nerve to even go to the mailbox. The task was relegated to Emily and Mickey, who sorted pipeline mail into two piles: one of correspondence advertising the pipeline as “A PATHWAY TO PROSPERITY” and the other a “save” pile containing more-important letters, which almost always asked permission to survey her property. So far, Cochran had ignored those letters. But she noticed near the bottom of the page was often a reminder that Virginia law gave Dominion, a public utility, the right to enter her property whenever it wanted.

Dominion’s statements to the media said surveyors wouldn’t enter any property unless granted permission, which might have been for the best since Cochran had instructed a neighbor armed with an assault rifle to watch her land. And, as she reminded Dominion employees, she had dogs and “they all have teeth.”

In Dominion’s communication to landowners — at public meetings or in interviews — the company insisted surveys were the best way for it to avoid anything of value that wasn’t obvious from satellite images: wells and family burial plots, for example. Along the entire route, 85 percent of landowners had allowed surveys, Dominion said, but in Nelson County the percentage was less than 40.

If the pipeline was approved, which was expected, Dominion could seize rights of way with eminent domain. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the agency responsible for approving interstate pipeline applications, could also reject the proposal, but even anti-pipeline activists considered this unlikely.

“NO PIPELINE” yard signs proliferated through the county, and informal networks sprung up to spread information. Several anti-pipeline groups organized, each with a slightly different flavor of resistance: One group was led by wealthy, well-connected transplants from Washington and held invitation-only meetings. Another espoused a familiar Sierra Club-esque environmentalism. And another group, which spoke more to Cochran’s ideals, took a more adversarial and creative intransigence; its tactics included “correcting” statements on the Atlantic Coast Pipeline Facebook page and offering a unique babysitting service: Volunteers would watch your house while you were away to prevent Dominion from surveying. The D.C. transplants, several of whom had built careers as lobbyists, claimed to have the most pragmatic stance: not objecting to the pipeline on the whole but trying to get it re-routed away from their pristine county.

“These connections have to go through private property,” Susan Tierney says. “People feel like their constitutional rights are being taken away.”

As Cochran spent her days driving to job sites, she pondered what was going on inside her community.

“We’ve been telling everybody all along, you don’t know where this is gonna go,” she said. “Everybody needs to stay united and fight the pipeline.”

No other location along the route was putting up even close to the same level of fight as Nelson County. News outlets began referring to it as “the epicenter of resistance.”

Heidi Cochran at home with her son, Mickey, 17. She refused to allow Dominion to survey her property and instructed an armed neighbor to watch her land. (Nikki Kahn/The Washington Post)

One of Dominion’s employees who had to face an exasperated Nelson County was Brittany Moody, manager of pipeline engineering.

At public events, Moody talked with landowners and poked an iPad tethered to her palm. She was among those who had chosen the pipeline’s route through Nelson County.

She was from the fracking boomtown of Buckhannon, W.Va. Her property had a fracking well; her home was within eyesight of where the pipeline might be built.

Moody was a certified coal miner whose first job was to investigate the 2006 Sago Mine explosion that trapped 13 miners, killing 12. Part of the mine was beneath her property.

“[Where] I grew up as a kid, my farm had a 36-inch pipeline right behind the house,” she said. “So I’ve just grown up around them.”

She tried to be understanding. “I’m good with trying to explain what all goes into it because I design them,” she said. But that didn’t necessarily make the process easy. One man at a pipeline open house whispered in her ear, “You know you’re not safe here, right?”

While she acknowledged Nelson’s angriest landowners had “legitimate concerns,” she also acknowledged that “Getting yelled at all the time and being called a liar is no fun.”

“When we begin planning the route we draw a straight line,” Moody said. “I’m looking for structures, topography. If it’s going to destroy your way of living, we’ll shift it and we will try to work with you. But the thing is, it’s got to go somewhere.”

Of the 245 lawsuits Dominion had brought or was planning to bring against landowners to get survey access, half were in Nelson County. Cochran knew her turn was coming. She began to compulsively check the county clerk’s website for the official posting.

On a January evening in 2015, Cochran traveled a short way to a session on how to oppose the pipeline, which was held in an old elementary school. She happened to enter at the same time as Rick Cornelius, one of the lawyers who was presenting that evening.

“So how do we stand with this, you think?” she asked him.

“How do we stand, my dear?” he asked. “We stand very early in the process. We still have two more years to go.”

Cochran’s chin dropped to her chest.

The first lawyer to speak advised them to choose an attorney wisely: “You’re gonna be through hard times together,” he said. “Make sure you get one you like.”

Next, Cornelius told the crowd that when writing to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission , property owners should say they would never willingly allow the pipeline on their land — that property would need to be seized through eminent domain.

“The more of you that are willing to say that, the better,” he said, “because that’s going to weigh heavily on FERC’s decision about whether or not this is, quote, in the public interest.”

Cochran wrote that down on scrap paper.

A man with a ponytail and a white beard down to his chest stepped up. He had a guitar and told the crowd he was going to teach them an anti-pipeline folk song to sing at Dominion’s next info session — as disruptively as possible.

“I was at [Dominion’s] last meeting,” he said. “They talked down to us. No one listened to us. So we need to teach them a lesson, and I’m hiring you all to be in my chorus.”

Sheets of lyrics were passed out, and he shouted at the crowd to “Sing!”

We don’t want your pipeline, we don’t want your pipeline

We’ll take the sunshine, the water and the wind.

We’re gonna put a stop sign on Dominion’s pipeline

Go tell your neighbors, go tell your friends.

Cochran’s 16-acre property includes a large field, two horse pastures, a small pond and a hay barn. She hopes to build homes on the land for her children one day. (Nikki Kahn/The Washington Post)

The expansion of pipeline infrastructure is what Susan Tierney calls a “big, tough situation” for places like Nelson County.

“People start moving to the corners of the room,” says Tierney. What we have, she says, becomes “a lot of people opposing things.”

So where were the diviners of reasonable common ground?

They existed, she says, but out of the public eye “in conference rooms where they’re trying to negotiate some calm or rational middle … [helping to] site the energy facilities in a way that is gentle on the environment.”

It turned out a pipeline whisperer was already on the Dominion payroll.

Bob Burnley is the former head of Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality, the state’s EPA equivalent. Partially retired, he’s now an environmental consultant. In the past, he says, he has opposed projects like the pipeline.

But he was going to help build this one.

In May 2015, Burnley was touring one of the company’s new natural gas power plants in Waynesboro, Va., the facility so new it sparkled in the sun. Burnley marveled. “I grew up professionally with big, nasty coal-fired power plants,” he said. “This is a huge step in the right direction. Replacing [coal] with gas is the only thing that makes sense right now.”

Dominion had contracted him, he said, “to help them understand what the environmental issues are and why the opponents are so opposed.”

After visiting the Waynesboro plant, Burnley hiked the Appalachian Trail a few miles south, stopping at an overlook in George Washington National Forest. The rock outcrop was close to where the pipeline would cross the trail while it traveled more than 30 miles through national forest. These areas, he said, had inspired him to take the pipeline as a client.

“It’s going through some incredibly special places, untouched lands,” he said. “Dominion and its partners are going to have to do a very, very good job at making sure that there is no permanent impacts to any of those things.”

The trees below were a carpet of springtime green.

“My instincts tell me that this pipeline is going to be built,” he said. “I think it’s more productive to work on the side of those who are trying to do a good job with it rather than wasting energy trying to keep it from being built.”

The morning after the anti-pipeline meeting, Cochran drove to Charlottesville in her pickup. A large project she was wiring had to go before the county’s Planning and Zoning Department, and after pulling into the parking lot of Eck Supply Co., she went in to chat with the staff.

They talked about the looming lawsuits. She had yet to check today to see if Dominion had officially sued her, she told them. Then she stepped into the manager’s office and quickly unfurled blueprints on his desk.

“Normally,” she said, “an engineer would have designed this, okay? But I don’t have that luxury.”

They were interrupted by a call from her son, Mickey, who wanted to know where to find parts for his pickup truck. It was in need of repair after a recent bout of “hooking,” an activity meant for “seeing who has the baddest truck.” This involves tying the rear bumpers of two trucks together, then driving them in opposite directions until one is either pulled backward or comes apart catastrophically. Cochran told him to call a neighbor and returned to the schematics. When she was satisfied with the design, she headed out to the parking lot, pulling her phone from her pocket to scan the county clerk’s website.

“Yeah,” she said, her face clenched with hurt. “Yep, they got us today. Son of a b—-.”

“Now I can’t even think,” she said.

The litigious circle widened before her eyes. “Gary Bryant got it, Pat Beasley got it, I got it, Sammy got it. … I’m pissed. Somehow this doesn’t feel real American, you know that?”

She went back inside to find her friend Mark, an employee she’d spoken with on her way in. She held up her phone. “They got me,” she said.

He leaned in close. “There you are,” he said.

“I just found out,” she said, her voice cracking.

“You’ll be okay,” he said and put his arms around her. “You’ll get through this, honey, I promise. It’s all a part of life, okay?”

She couldn’t hold back the tears.

“We’ll get stronger,” he said, hugging her close. “Imagine that. Through all this we’ll get stronger.”

Visitors to the farmers market in Nelson County sign a petition to prevent Dominion Energy from installing the pipeline. (Jay Westcott/Jay Westcott/For The Washington Post)

Dominion’s website focuses on the relative safety of gas pipelines, pointing out “the number of incidents nationally is very small given the more than 300,000 miles of natural gas pipelines in the country.”

Pipeline operators are required by the U.S. Department of Transportation to self-report “incidents.” Incidents involving hospitalization or death are trending downward toward fewer fatalities (53 deaths in 1996, 9 deaths in 2015) and fewer injuries (127 to 50). But when that parameter widens to include “oil spills, fires, explosions and economic damage of $50,000 or more ‘in 1984 dollars’ ” ($115,000 today), the trend goes the other direction. Over 20 years the department has recorded 5,670 such events, with 324 reported in 2015, compared with 252 in 2012.

Cochran knew about what happened in San Bruno, Calif. In September 2010, the San Francisco suburb had a 30-inch pipeline explode beneath it, igniting a fire that destroyed a neighborhood block. West Coast utility Pacific Gas and Electric was fined $1.6 billion for shoddy maintenance. Fifty-one were injured, and eight were killed.

Pipeline: Tension at Meetings

Embed Share

Play Video1:38

(The Washington Post)

As part of the pipeline approval process, Dominion was required to hold public information sessions. At one, Cochran found a Dominion employee and got right to the point: “What’s the kill zone of a 42-inch pipeline?” she asked.

He told her the proper term was “potential impact radius,” and that it was 1,100 feet on either side of the pipe.

“The odds of survival if there was an explosion?” she asked.

He said the potential impact radius wasn’t about certain death; it was about “flying debris, rocks and all that.”

“And flames?”

“Could be. But probably not,” he said. “Flames will typically go straight up. But if there’s a building or something within that, it could get hot enough to catch fire.”

“So with my house 50 feet from there?” she said, hands outstretched.

He nodded but didn’t answer.

“What do you think the impact to my house would be? Heavily impacted?”

“Could be.”

“And if my children were home? Heavily impacted?” she said.

“Could be,” he said again.

Next she walked to FERC’s table.

“Do you ever look at situations like this,” she asked a FERC representative, “where a pipeline would be so close to a home?”

The representative told her they would fly the route, look at maps, make the best decision possible. Cochran handed over maps of her property along with a letter she had written that made clear the personal costs of the pipeline. Other people wanted to tell their own stories and started to push in from behind.

“Please look at it seriously,” she told him. “My heart and soul is in this. My family is in this. And I’m not the only one.” Emily stood at her mother’s side and cried.

As she walked away, a group on the other side of the room began to clap rhythmically — the anti-pipeline protest song was starting.

We’re gonna put a stop sign on Dominion’s pipeline

Go tell your neighbors, go tell your friends.

FERC held “scoping meetings” along the pipeline’s path. Members of the public took turns giving three-minute speeches, their words becoming part of the data FERC would use to make their decision. When Cochran arrived she went directly to the table designated for signing up to speak. Hundreds did. Far too many to fit into the allotted time.

When the speakers began, 19 of the first 20 were pro-pipeline. Many wore Dominion’s pro-pipeline stickers that read “Energy Jobs for Virginia.” Anti-pipeline people shouted them down. Some angrily accused FERC staff of giving Dominion early access to the sign-up sheet, so they’d speak before the TV crews left.

“People were signed up at the time they arrived at the facility and put their names on the speakers’ list,” the FERC representative said into the microphone. (Dominion had, in fact, front-loaded the meeting with pro-pipeline speakers, according to Dominion spokesman Jim Norvelle.

In an email, he wrote that interns had signed up pro-pipeline speakers: “It should surprise no one that we decided we could not let one side dominate the debate.”)

The string of pro-pipeline speakers continued.

“Oh, my god,” said Cochran as one after another came to the podium. “This is unreal.”

One “pro” speaker noted Nelson County needed the jobs, prompting a man to yell: “Is there anyone who needs a job in here? I will hire them right now!”

“Silence the interruptions,” warned a FERC employee.

When Cochran spoke an hour later, she read from notes that trembled in her hand.

“The odds, they say, would be small for any explosion. I am not a gambling person, but I believe the odds are better of no explosion if a pipeline did not exist.”

When the event finally finished, sheriff’s officers escorted the FERC employees outside. Cochran knew one of the deputies and asked why.

“Someone made a death threat against them,” he told her.

Cochran knew that if they succeeded in pushing the pipeline out of Nelson County, it would only mean it would be built in a different county and routed through different back yards.

“It bothers me that I only cared about this when it was in my back yard, that I never got involved when it was happening to someone else,” she said. “It may be a done deal with me, but that’s who I’m doing this for now: for the next person who’s going to have a pipeline built in their back yard.”

The pipeline also made her aware of where the gas would be coming from, something she hadn’t considered before. She had been reading about fracking and the possible dangers it sometimes posed to drinking water, and had decided to see it for herself. She had also been tracking an anti-FERC protest group called Beyond Extreme Energy, or BXE, which had formed simply to attack FERC and the growth of energy infrastructure. The group was planning protests at FERC headquarters in the District that May.

The next morning, Cochran and a fellow pipeline resister named Marilyn Shifflett drove 150 miles to Buckhannon, W.Va., in an area known as the Marcellus Shale; these were to be “the headwaters,” of sorts, of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

A local activist acted as their tour guide. From the back seat he directed Cochran down the county’s endless gravel roads.

Cochran and Shifflett were stunned by all the fracking wells and protruding sections of natural gas pipe. There were “flare stacks,” devices that burned excess gas high in the air.

They rounded a bend, and on the other side of the ravine was a hill about the size of Cochran’s own hill. But this one looked much different.

“So that’s what a 100-foot right of way looks like?” she gasped. “Oh, my god!”

She pulled over and leapt from the truck. “I gotta see this,” she said.

A wide swath of mature hardwoods had been cut, the trees left where they fell. It ran from the top down into the valley. This clearing, the activist told them, was a right of way for a 36-inch pipeline.

While her companions talked, Cochran just stood and stared at the sight before her in disbelief.

Pipeline: Sense of Heidi

Embed Share

Play Video2:37

(The Washington Post)

In spring 2015, Cochran was pleasantly surprised by two incidents. The first was Mickey’s high school graduation.

“I honestly didn’t think he was going to,” she admitted afterward. Mother and son were in the school parking lot, talking with friends and leaning against the hood of his Toyota pickup. A bumper sticker between them read “NO PIPELINE.”

“I’m proud of you, bud,” she said and hugged Mickey. He had been studying to be an auto mechanic. Since February he’d been working at a garage, so close to home that he sometimes drove a riding lawn mower to work.

But the bigger surprise had come four days earlier: Dominion announced it was championing a route that would require the company to drill a tunnel under the Appalachian Trail because it would have “less impact to environmental, historic and cultural resources than the initially-proposed route,” a statement read.

When she heard the news that Dominion wanted to relocate the pipeline off her property, Cochran dismissed it as a ruse.

“I still think they want us to drop our guard and have division,” she said. She knew Dominion had yet to submit its application to FERC. Until then, Dominion’s preference was not absolute. “I don’t trust them.”

Moreover, this newest route called for the pipeline to pass within 100 yards of the Wintergreen Resort, the economic engine of not only the county but Cochran’s own wallet — many residents were her clients.

Wintergreen’s homeowners association wrote FERC that the pipeline’s route would be much better if it was returned back to the route that would run through Glass Hollow, a suggestion that outraged Cochran.

Despite this development, Cochran still planned to attend the Memorial Day protests in Washington. It had been 40 years since she had attended a protest of this scale and at least a decade since she had been to the District.

Cochran gathered the bed linens she would need to sleep on the floor of St. Stephen Church in Columbia Heights. She was getting a ride with a local woman, Vicki Wheaton.

Wheaton arrived in a Hyundai hatchback overflowing with protest paraphernalia. Cochran stuffed her things in between.

“Well, this is an adventure,” Cochran said, taking a last look around. “I’m definitely gonna miss my mountains.”

Less than 24 hours later, Cochran and about 50 other protesters were marching four or five blocks from Union Station to FERC headquarters, where they were going to blockade the agency’s parking garage.

The protesters were an assortment of young and old; some wore lanyards and carried walkie-talkies used to orchestrate the event from a non-arrestable distance.

“Our government,” came the start of a call-and-response chant, “is under attack!” Presumably the attackers were the nation’s major energy companies. “What’re we gonna do?!”

“Stand up, fight back!” yelled Cochran. She carried a poster that read: PROTECT OUR TOWNS.

Organizers eventually directed everyone to the middle of North Capitol Street. There a small group of protesters had formed a tight circle around a strangely shaped object. When Cochran got close she saw it was a large metal tepee, known as a “tripod” in the theater of civil disobedience. In morning traffic, the protesters had managed to erect three 15-foot metal tubes whose apex held a woman hanging by a rock-climbing harness. The design was predicated on the fact that if she came down any way but voluntarily, the structure would collapse and injure her and anyone underneath it.

Soon the protesters’ bullhorn came out, and BXE organizers tracked down people they thought would be compelling voices.

Cochran was one of the first. “Say who you are and where you’re from,” said a middle-aged man with the bullhorn. Cochran became nervous.

Pipeline: DC protest

Embed Share

Play Video0:34

(The Washington Post)

“My name is Heidi Cochran,” she began. “I’m from Afton, Virginia, in Nelson County. They want to put a pipeline through our county. Just last week we became the alternate route, but I’m not trusting of Dominion.”

“You go, girl!” someone yelled.

“In Nelson County, 69 percent of impacted landowners have denied the right to survey for Dominion,” she said to cheers. Then she told her story: the lost building sites, the saga of challenging Dominion over the past year, reasons she thought more fossil fuel infrastructure was a bad idea. As she reached her conclusion, her voice was resolute. “I will continue to fight, I will not let them on my property.” And then: “And I’ve painted a nice big sign on my barn that says, ‘No pipeline.’ ”

She lowered the bullhorn, returned it to its owner, turned and walked away.

Twelve hours later at St. Stephen, Cochran, Wheaton and a woman from Nelson County named Arlene Hueholt sat on an inflatable mattress set up in the nave of the church. They all wore their pajamas.

Hueholt felt the day had been “somewhat ineffective” and lamented that they weren’t able to stop FERC employees from entering their building.

Cochran was surprised. “I thought they did really good today.”

Hueholt shook her head. “We’re gonna have to occupy that building eventually.”

In September, Dominion formally filed its certificate of application. The 30,000-page proposal made it official: The company preference was to use the route under the Appalachian Trail eight miles from Cochran’s home.

Dominion’s proposal allowed affected parties such as the U.S. Forest Service to perform in-depth analyses of the exact path. Within months the Forest Service twice forced Dominion to change the route in both the Monongahela and George Washington national forests to avoid endangered salamander habitats. That meant 249 new landowners receiving notice.

“Sometimes when I think about the people who are just starting to go through all this,” said Cochran, “it brings me to tears.”

“Sometimes when I think about the people who are just starting to go through all this,” Cochran says, “it brings me to tears.” (Jay Westcott/Jay Westcott/For The Washington Post)

On a morning in late February this year — one year and nine months since finding Dominion’s letter in her mailbox — Cochran was up before dawn to feed the animals. The land was soft with rain and snowmelt.

When this all started, 2016 was to be the year pipeline construction began. Now FERC was expected to render its verdict in the beginning of 2017.

Cochran was pushed to waitressing four to five nights a week to support her eldest daughter, Sage, who was out of work and living in Nelson County again.

As a result, Cochran had had to scale back anti-pipeline activities of late, though she was still lobbying at the state Capitol in Richmond and attending court proceedings of holdout landowners sued by Dominion. She was also planning to attend more BXE protests of FERC headquarters.

And there was another addition to the household: Emily’s boyfriend had moved in with them. Cochran’s 1,300-square-foot house was feeling smaller than ever. Mickey needed to move out. Cochran had a trailer hauled onto the field out back. And there were two other homes to build: one for Emily and one for Erica. Everyone, it seemed, was moving home.

Mickey joined her in the field.

“If we put the trailer over there,” said Cochran, pointing toward the pond, “we can combine the septic systems.”

She and Mickey walked toward two of their horses as the horses walked toward them.

A delicate mist rolled in, much as it had the first time she stood here. But she was different now. The pipeline fight had taken her far beyond Glass Hollow and returned her back again.

She was more resilient, and also more hardened — though she still couldn’t bring herself to go to the mailbox. Above all, she had never felt more connected to the promise of her land.

“I finally feel a little better, but I’m still afraid,” she said. “It’s not a done deal.”

The sky grew suddenly dark — in a few minutes it would be raining as hard as rain can fall. Still, she turned and said with a smile, “But isn’t that a pretty view?”

Follow Us!