LABYRINTHS FOR HEALTHCARE: APPROACH WITH CAUTION

Labyrinths have become increasingly popular in healthcare settings like hospitals, outpatient clinics, hospices, and elder care facilities. Designers often include them in their plans, sometimes encouraged by the client or the funding donor. However, labyrinths are not always appropriate for healthcare gardens. While they can be very successful, there are now too many examples of labyrinths that are poorly sited, badly designed, or just shouldn’t be there. As with any element of a healthcare garden, the design intention must be to provide what will most benefit the users–patients, visitors, and staff. Clare Cooper Marcus and I discuss this issue in our book Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces, from which some of this text is excerpted. Please understand: I have nothing against labyrinths per se. In fact, in the right place and context, I think they are wonderful and very much enjoy walking them.

First, What is a Labyrinth?

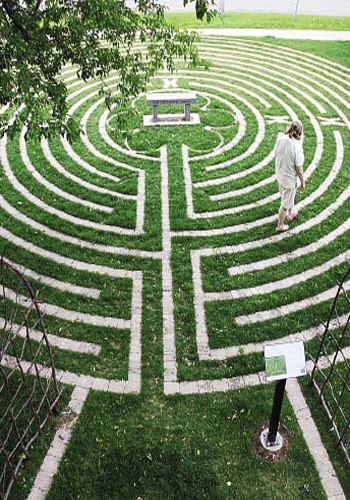

The classical labyrinth consists of a continuous path that winds in circles into a center and out again. This basic form dates from antiquity and is intended for contemplative walking. A labyrinth is sometimes erroneously referred to as a maze, which consists of a complex system of pathways between tall hedges, with the purpose of getting people lost. The aim of a maze is playful diversion, whereas the aim of the labyrinth is to offer the user a walking path of quiet reflection.

The Labyrinth Trend

I’m not sure what led to the uptick in labyrinths in healthcare gardens (as well as other gardens), but here are some guesses:

Labyrinths are immediately recognizable as contemplative spaces that encourage silent walking and meditation. Like “Zen gardens,” they symbolize peace and relaxation.

They are usually easy to install and, unlike planting beds, require very little maintenance. However, most labyrinths are paved and according to many research studies, people prefer less paving and more plants in healing gardens.

Here is why labyrinths are often not the right choice for healthcare gardens:

They take up a lot of space that could be used for plants, a covered gathering area, or a more flexible activity space. Because people view labyrinths as somewhat sacred, they are reluctant to walk across them to get from Point A to Point B. Unless the garden is quite large, a labyrinth is probably not the best use of space.

Labyrinths are usually not sheltered by trees or another shade structure. People in hospitals – especially patients – are extremely vulnerable to sun and glare.

They take a long time to walk, which may not be good or even possible for some patients.

They are usually not wheelchair accessible. So people who have limited mobility — anyone in a wheelchair, scooter, walker, or even with a large stroller — can’t use them, which, especially in a hospital environment, is rather sad.

How to Design a Labyrinth for a Healthcare Garden

If you plan on including a labyrinth in a healthcare garden, consider the following design guidelines from Therapeutic Landscapes:

The classical labyrinth consists of 11, 7, or 5 concentric circles. The path of the 11-circuit labyrinth is 860-feet long and thus should not be considered for a healthcare garden. Walking that far would likely tax the energy of patients or the time of visitors or staff. The 7- or 5-circuit labyrinth is more appropriate, both in terms of the length of the path and in terms of the space it claims.

People walking a labyrinth are in a contemplative, introspective mood and do not want to be stared at. Site the labyrinth in a secluded location out of sight of other garden users and nearby windows.

Since some people view the process of walking a labyrinth to be a spiritual experience, site it where others will not be forced to walk across to get from one destination to another.

Since many people may be unfamiliar with the purpose of a labyrinth, provide information nearby indicating how to walk the path.

Consider a “finger labyrinth” – they take up far less room and can still provide people with a meditative practice.

This guest post is by Naomi Sachs, ASLA, and Clare Cooper Marcus, Hon ASLA. Sachs is founder of the Therapeutic Landscapes Network and Naomi Sachs Design. Some of the text for this post was excerpted with permission from the publisher, Wiley, from Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces by Clare Cooper Marcus and Naomi A. Sachs. Copyright 2014.

Posted in Gardens, Health + Design, Landscape Architecture | 3 Comments »

Follow Us!