SERENBE’S NEW WELLNESS DISTRICT FEATURES A FOOD FOREST

Deep in the woods southwest of Atlanta, Serenbe is a unique designed community — a mixed-use development, with clusters of villages comprised of townhouses and apartments fueled by solar panels and heated and cooled by geothermal systems, and vast open spaces with organic farms, natural waste water treatment systems, and preserved forests. A leader in the “agrihood” movement, which calls for agriculture-centric community development, Serenbe is now moving into wellness with its new development called Mado.

On a tour of the new town, which will add 480 homes, including some assisted living cottages, to the 1,400 that already house some 3,500 people, Serenbe founder Steven Nygren explained how his vision of wellness was inspired by the sustainable Swedish city of Malmö. He and his wife Marie traveled there, and they brought back lots of photographs, which they then gave to their planners, architects, and landscape architects.

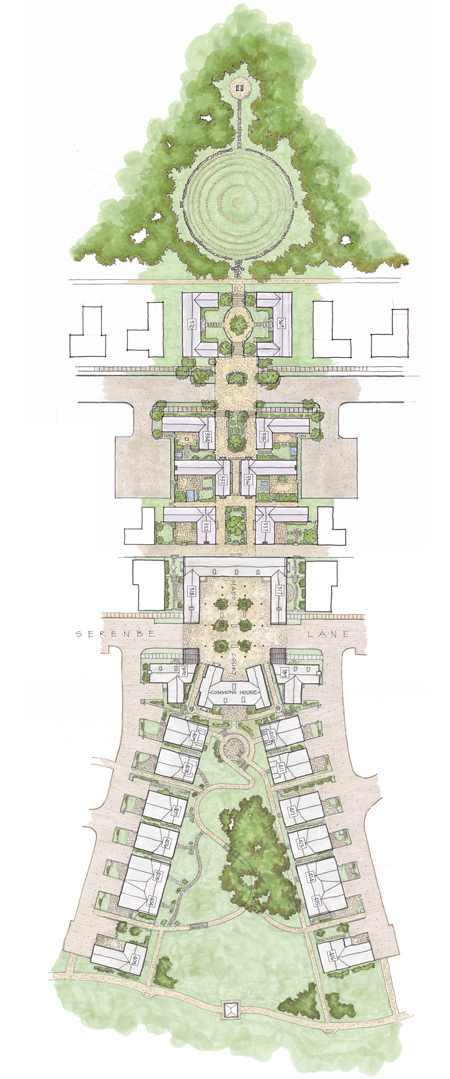

The community now under construction is organized around common spaces set in gardens. Nygren fears a scenario in which you have two older residents out on their porches, but both are waiting for the other to invite them over. In Mado, the ground-level shared patios may create more opportunities for interaction.

Also, Nygren reached an interesting conclusion from his trip to Malmö: “They always connect streets into nature.” He decided to recreate that relationship in Mado, organizing the housing and common spaces along a central axis with ends that extend into nature trails.

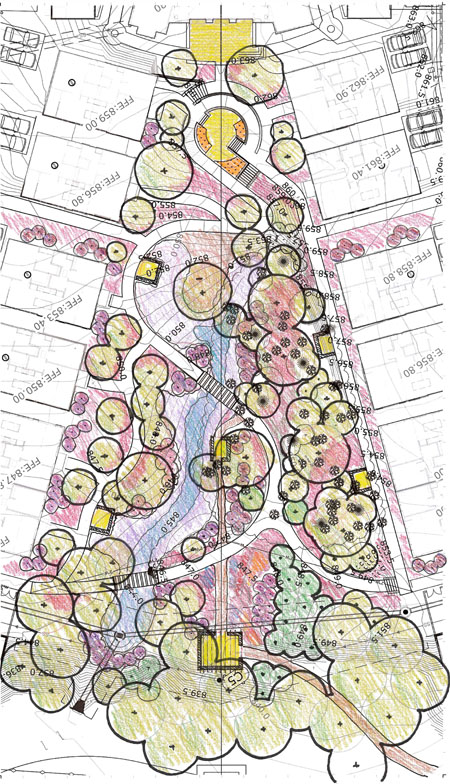

Once this central organizational structure was decided upon, they brought in landscape architect and University of Georgia professor Alfred Vick, ASLA, who then created an innovative “food forest” to realize the concept of wellness in landscape form (see the bottom portion of the image above). It will function as an accessible outdoor living room, given throughout the space the gradient is less than 5 percent. It’s also a place where people can gather and also learn how to forage in the wider Serenbe landscape (see a close-up of its design below).

Vick said his vision was of a “edible ecosystem, an intentional system for human food production.” Using the natural Piedmont ecosystem as the base, Vick is creating a designer ecosystem of edible or medicinal plants, with a ground layer, understory, and canopy that also incorporates plants with cultural meaning and a legacy of use by indigenous American Indian tribes.

He imagines visitors to the forest foraging for berries, fruits, and nuts, including serviceberries, blueberries, mulberries, and chickasaw plums, as well as acorn and hickory nuts, which can be processed and turned into foods. Mado residents and chefs can harvest the young, tender leaves of cutleaf coneflowers, which are related to black-eyed susans. Or reach up to an arbor, which will be covered in Muscadine grape vines and passion flowers. Or take some Jerusalem artichokes, which were used by Cherokee Indians and today cooked as a potato substitute. Or pluck rosemary or mint from an herb circle. Vick left out peach and apple trees because they require fungicides.

“The primary goal is to engage residents,” Vick explained. There will be interpretive guides to explain how plants can be consumed, which will also “help encourage wider foraging when they are out in the Serenbe landscape.” Nygren wants everyone in the community connected to the productive cycle of nature and to know when the serviceberries, blueberries, figs are ready to be picked.

And the landscape is also designed to both provide a safe boundary — so grandparents can let kids roam — but also provide a natural extension into the rest of the landscape. While the Mado designs are still being developed, we hope that universal design principles, which call for fully-accessible seating and nearby restrooms, will be incorporated to ensure an 80-year old as well as an 8-year old can comfortably access and enjoy the landscape.

Learn more about Serenbe in this interview conducted with Nygren in 2015.

Follow Us!