THE NEW LANDSCAPE DECLARATION: VISIONS FOR THE NEXT 50 YEARS

Over the next 50 years, landscape architects must coordinate their actions globally to fight climate change, help communities adapt to a changing world, bring artful and sustainable parks and open spaces to every community rich or poor, preserve cultural landscape heritage, and sustain all forms of life on Earth. These were the central messages that came out the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF)‘s New Landscape Declaration: Summit on Landscape Architecture and the Future in Philadelphia, which was attended by over 700 landscape architects.

The speakers used declarations and short idea-packed talks, and attendees used cards, polls, and an interactive question and commenting app to provide input into a new declaration — a vision to guide the efforts of landscape architects to 2066.

As the 50th anniversary of the original declaration in 1966, many landscape architects looked back to see what has been achieved over the past 50 years. At the same time, through a series of bold statements, they created an ambitious global vision moving forward. As Barbara Deutsch, FASLA, president of LAF, believes: “We are now entering the age of landscape architecture.”

While not a comprehensive review of all the declarations, here are some highlights of the visions of what landscape architects must work to achieve over the next 50 years:

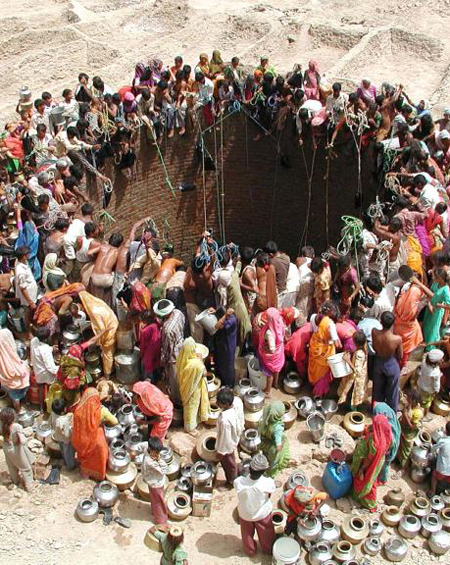

Landscape architects must address the “serious issues of air, water, food, and waste” in developing countries

Alpa Nawre, ASLA, assistant professor of landscape architecture, Kansas State University, called for landscape architects to focus their efforts on the developing world, where the bulk of the current population and most of the future population growth will occur. Today, of the 7.2 billion people on Earth, some 6 billion live in developing countries. There, some 100 million lack access to clean water. The global population is expected to reach 9.6 billion in coming decades, with 400 million added mostly to the cities of the global south. “To accommodate these billions, we must design better landscape systems for resource management.”

Gerdo Aquino, FASLA, CEO of the SWA Group, echoed that sentiment, arguing that “in the future, there will be much more stringent regulations on natural resources” as they become rarer and more valuable. Landscape architects will play a larger role in valuing and managing those resources.

Christophe Girot, chair of landscape architecture, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, similarly saw the need for “new topical landscapes” for the 9.6 billion who will inhabit the Earth. We must “react, think creatively, and find solutions.”

Landscape architects must improve upon urbanization-as-usual

Instead of pursuing idealized visions of parks and green space that may result in “tidy little ornaments of green that make liberals feel good,” Chris Marcinkowski, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania and partner at PORT Urbanism, said landscape architects must “work with the underlying systems of urbanization and adapt them,” softening them in an era when 1 billion people live in cities.

James Corner, ASLA, founder of James Corner Field Operations, pushed for accelerating urbanization in order to protect surrounding nature. “If you love nature, live in the city.” He called for landscape architects to “embed beauty and pleasure in cities” in the forms of parks and gardens, because we need to make it “so that people should want to live in cities.” Landscape architects must envision a denser urban world as well, and “shape the form of the future city.” His vision of the future city is a “garden city” that takes advantage of the “landscape imagination.” And Charles Waldheim, Hon. ASLA, chair of landscape architecture at Harvard University Graduate School of Design, and Henri Bava founding partner, Agence TER, similarly made the case for a new “landscape-led urbanism” rooted in ecological processes.

David Gouverneur, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania, called for applying novel approaches to the slums in which he works in Venezuela, where the conventional planning and design process fails. He proposed retrofitting slums through his “informal armature approach,” which can create both pathways and communal nodes but also areas of flexible growth that allows “locals to invade and occupy.” He argued that new forms of planning and design can better meet the needs of the vast informal communities in the world.

And Kate Orff, ASLA, founder of SCAPE, explained how her community-centric approach “creates a scaffolding for meaningful participation that is an active generator of social life.” For her, it’s all about “linking the social to the ecological and scaling that up for communities.”

Carl Steinitz, Hon. ASLA, professor emeritus of landscape architecture and planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, also called for all landscape architects to get more active at the urban and regional scales. “That’s where society needs us the most.”

Landscape architects must create a future for wild nature

“The landscape has been broken into fragments. We need a more inclusive approach, a new philosophical relationship between humanity and nature,” said Feng Han, director, department of landscape studies, Tongji University in Shanghai. That new approach must be rooted in “just landscape planning and design.”

Randolph Hester Jr., FASLA, director, Center for Ecological Democracy, and professor emeritus, University of California, Berkeley, made a similar and compelling argument, saying that “justice and beauty must be found together in the landscape.” The landscape itself is a “community, with the ecological and cultural being indivisible.”

A central part of achieving that just landscape planning and design approach is to better respect the other 2.5 million known species on the planet, argued Nina-Marie Lister, Hon. ASLA, professor at Ryerson University. “We must think of the quality of being for them, too.” To protect their homes, landscape architects must lead the charge in “re-establishing the role of the wild.” E.O. Wilson, in his most recent book, Half Earth, calls for preserving half of the planet for the other species. “That kind of goal is a blunt instrument. Now we need to design what that looks like. We need a planetary strategy that connects remnant fragments. We can create a global mosaic that will be the foundation of a next wave of conservation.”

A key part of those mosaics will be designed sustainable landscapes, said Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, FASLA, who argued that “sustainability needs to be addressed in every landscape” moving forward. “We must keep every scrap of nature” by certifying projects with systems like SITES.

And in case anyone forgot the essential message: Laurie Olin, FASLA, founder of OLIN, argued that “everything comes from nature and is inspired by nature.”

Landscape architects must dramatically increase in number

Given landscape architects relatively small numbers — there are estimated to be less than 80,000 worldwide — Martha Fajardo, International ASLA, CEO, Grupo Verde, said each must “become ambassadors for the landscape,” speaking loudly wherever they go.

But Mario Schjetnan, FASLA, Mexico’s leading landscape architect, said that may not be enough and more numbers are needed. For example, while there are more than 150,000 architects in Mexico, there are only 1,000 landscape architects.

He said: “There are not enough landscape architects in the developing world. And we need a global perspective. The U.S. and Euro-centric perspective must change. More landscape architects from the developing world studying in the U.S. and Europe need to return to their countries and help.”

Landscape architects must diversify themselves fast

“Minorities are woefully underrepresented” in the field of landscape architecture, argued Gina Ford, ASLA, a partner at Sasaki. “The black and Hispanic populations in the U.S. are growing.” How can we address this? Ford called for the highest levels of academic and firm leadership to bring in and hire minorities. “It’s not about getting warm, fuzzy feelings; it’s about innovation. Diversity begets innovation. Diverse staff resonate with diverse clients. We must diversify to create a shared vision for the future.”

Landscape architects must get even more political

Patricia O’Donnell, FASLA, founder of Heritage Landscapes, who is active in UNESCO, ICOMOS, and other international organizations, said the first step is for landscape architects to “show up” and engage in political debates. Then, they must “collaborate to be relevant.” Working within these complicated international fora, O’Donnell herself pushes for “connecting biological diversity with cultural diversity” and encouraging these organizations to value cultural landscapes. To be more relevant, she said, landscape architects should further align their efforts with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Kongjian Yu, FASLA, founder of Turenscape, may be the epitome of the political landscape architect. His work spans planning and design across mainland China, but he spends a good amount of his time and energy on persuading thousands of local mayors and senior governmental leaders alike on the value of “planning for ecological security.” He called for landscape architects to “think big — at the local, regional, and national scales” — and to influence decision-makers.

Martha Schwartz, FASLA, founder of Martha Schwartz Partners, who is an active advocate and commentator in the UK, where she now lives, threw down the gauntlet, calling for landscape architects to form a political wing that will urge policymakers to fund bold research into geo-engineering techniques that can stave off the planetary emergency caused by climate change. At the same time, “we need to start a political agenda for a Manhattan project to reduce carbon emissions.” Schwartz sees ASLA pushing for climate rescue over the next 50 years, helping us to “buy the time for a second chance to live in balance with the Earth.” For her and others, climate action is the platform for landscape architecture for the next five decades.

And Kelly Shannon, chair of landscape architecture at the University of Southern California, International ASLA, made the case for “changing the unsustainable status quo and inspiring new social movements.” Landscape architects must become “essential game changers.”

Landscape architects must better leverage green infrastructure to achieve broader goals

Using their knowledge of systems, nature, and people, landscape architects must find new opportunities to regenerate poor communities that have been left out. Tim Duggan, ASLA, Phronesis, called for using green infrastructure as a wedge for creating opportunities. “In consent decree communities, green infrastructure can be leveraged to create wider urban regenerative processes.” Green infrastructure, as Duggan has shown, can become the catalyst for community development.

But to make this happen in New Orleans and Kansas City, he had to “lobby change at the decision-maker level and string together innovative financing mechanisms.” In other words, he had to wade into the broader economic and governmental systems to make change happen.

Landscape architects must keep design central to the human experience

Charles Birnbaum, FASLA, founder of The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), said a “holistic view” was needed, and that landscape architects can’t foresake the important role of art and design in the experience of landscape architecture by focusing exclusively on ecological values. “We need to put the value of landscape architect on the level of the artist.” Harriet Pattison, FASLA, helped him make the point in this segment of her TCLF oral history project:

Blaine Merker, ASLA, Gehl Studio, argued for “making humanism physical and celebrating the human condition” through well-designed space for people. “Plazas and parks increase social connection. This leads to deep sustainability and happiness that reinforce each other.”

Landscape architects must generate new fields of research and design to stay relevant

A fascinating idea: what is on the margins today may be at the center tomorrow. Dirk Sijmons, co-founder, H+N+S Landscape Architects, argued for landscape architects to get more deeply involved in what may be a marginal area for them now: the transition to clean energy. He showed his work animating the energy flows of off-shore wind farms in the North Sea. “We must develop new centers for the discipline.”

Landscape architects educators must “revolutionize the landscape architecture education system” and become more pragmatic

Kongjian Yu also called for the educational system to teach the aesthetic value of ecology and sustainability. “We need deep forms rooted in ecology, not shallow forms. Nature is the bedrock.” Yu calls landscape architecture an “art of survival” that will become increasingly relevant as the world’s problems only multiply. “We need to teach how landscapes can fight flooding, fire, drought, and produce food. We need to generate pragmatic knowledge and basic survival skills to open up new horizons.”

Marc Treib, professor of architecture emeritus, University of California, Berkeley, added that “the sustainable is not antithetical to the beautiful. We can elevate the pragmatic to the level of poetry.”

While these bold ideas do push the landscape architecture agenda forward, what was missing from the LAF event was some critical discussions on how to better collaborate with scientists, ecologists, developers, architects, urban planners, and engineers on forging a common vision that can increase their collective impact in the halls of power; the coming explosion of aging populations; the health benefits of nature — and how the desire for better health could become a central driver of demand for landscape architecture; and sustainable transportation and the future of mobility. Hopefully, we’ll see more on these as LAF continues to hone its vision.

Follow Us!