THE VISIBLE HAND OF THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT

Gina Ford, ASLA, a landscape architect and principal at Sasaki Associates, keeps coming back to the same question: “How do we make the hand of the landscape architect visible?” Ford posed the question during a lecture at North Carolina State University’s College of Design. She then identified two projects from the multidisciplinary Urban Studio she chairs at Sasaki that demonstrate just a few of the visible roles landscape architects play.

Ford and her team played the roles of planner and designer for Lawn on D in Boston, a 2.5-acre project that grew from Sasaki’s commission to create a master plan for the expansion of the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, which Ford called “this ginormous spaceship that landed in the seaport.” In the middle of what was then surface parking and scattered industrial buildings, Ford’s team imagined new development and open space to create meaningful connections between the waterfront, convention center, and the historic South Boston neighborhood.

“The community kept wanting open space, open space, open space,” Ford said. “The question was: How do you create open space that will appeal both to convention-goers, who are here for a weekend, and also to the South Boston community that wants to see this as an extension of their neighborhood?” She said,“this idea of the Lawn on D emerged. We created a landscape that’s temporary, so we can test some ideas about what a park might be like here and what resonates.”

After only nine months for design, bids, and construction, the Lawn on D opened in 2014 on a parking lot abutting the convention center at a cost of $10 per square foot. Using what Ford called “modest means,” the Lawn on D features lawn, asphalt, tennis court paint, a canvas tent, light fixtures, and minimal plants. The plan was to keep it open for about 18 months, to see what users liked and didn’t like, and then to collect design and programming ideas for a permanent open space that would be incorporated into the convention center expansion.

18 months later, the convention center expansion has stalled indefinitely due to budget constraints. But in that time, the Lawn on D has become a Boston landmark. Sasaki’s simple design template — green edges framing a path, a paved lighted plaza, a tent, and a big lawn — accommodate food trucks, movie screenings, concerts, art installations, snow chutes, and other creative, Boston-themed events dreamed up by the firm HR&A Advisors. Ford said one of the art installations — Swing Time by Höweler + Yoon Architecture — has become the selfie capital of Boston.

Ford’s team now faces the enviable challenge of how to retrofit and make permanent a space that was meant to last 18 months but instead became a beloved community destination, enlivening a part of town that used to be simply a midpoint between other iconic Boston neighborhoods.

Another project of Ford’s urban design studio is A Delta for All, the winning proposal from the Changing Course design competition, which seeks to “re-imagine a more sustainable Lower Mississippi River delta.” Sasaki joined a team of specialists led by Baird & Associates to answer the central question posed by the competition brief: As the coastal wetlands between New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico disappear at the rate of one football field per day, is it possible to save the cherished communities and ecosystems of the Lower Mississippi Delta?

Here the hand of the landscape architect was perhaps subtler but no less important. Ford’s role was to communicate — to consider the human element and then explain to stakeholders the function and impact of a proposed engineering marvel.

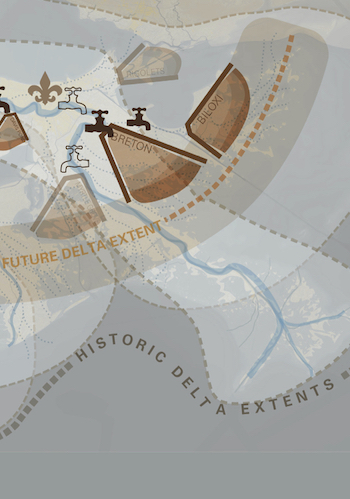

The plan devised by the team’s engineers and specialists, which boast expertise in everything from wetland structure and sediments to river navigation and oysters, essentially would undo the effects of human channeling of the Mississippi River. Ford explained that before human channeling, the river moved like a hose over the landscape, shifting its mouth over centuries, redistributing upstream sediments to create the wetlands as a series of ridge lines with freshwater basins in between. After human channeling, which created set channels, those valuable upstream sediments ended up running off into the Gulf of Mexico, bypassing the wetlands, therefore failing to replenish them.

A Delta for All proposes diverting the mouth of the Mississippi River and then feeding its water and sediment into neglected inter-tidal basins. Over time, “like spigots on a faucet,” the river mouth could be shifted to feed the inter-tidal basins in rotation, mimicking the natural shifts of the pre-channelized river.

If implemented, A Delta for All would be a complex undertaking, with major implications for communities and industries, natural ecosystems, and long-held ways of life. Ford’s team created graphics and a website to break down the issues, proposed solutions, and expected immediate and long-term benefits for coastal communities.

And they also tackled the challenge of possible re-locations for the wetland communities whose homes wouldn’t be spared. “Most of the federal programs to migrate people out of high-risk zones are just one household at a time, but as we came to understand, people in the delta live in these really tight-knit small communities,” Ford said. “So we suggested maybe there’s a way to phase their inland migration over time, providing some safe haven in the short term for small communities to move inland during storm events, and over time that inland safe haven could become a permanent home.” She added, “perhaps this is a way to start thinking about moving people in the right direction, over a larger period of time, together.”

These projects get to the heart of landscape architects’ role and Ford’s mission — to transform communities’ physical spaces in order to improve quality of life and nourish the human spirit, whether it’s at the scale of a new park in an evolving urban district or an entire region faced with deep ecological change. This transformation is visible.

This guest post is by Lindsey Naylor, Student ASLA, master’s of landscape architecture candidate, North Carolina State University.

Posted in Climate Change, Ecosystem Restoration, Green Infrastructure, Landscape Architecture, Public Spaces, Urban Redevelopment | Leave a Comment »

Follow Us!