Trolls Are Still Tweeting Christine Blasey Ford’s Address, and Twitter Hasn’t Stopped It

This article has been updated with a response from Twitter.

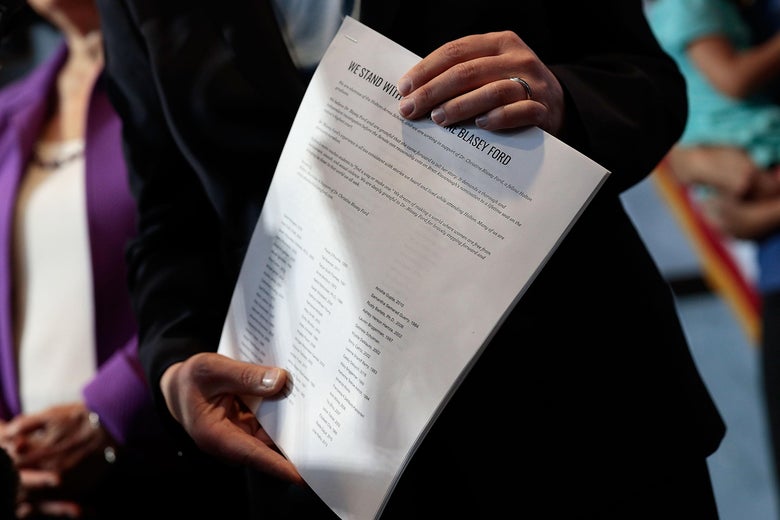

Since Christine Blasey Ford came forward Sunday as the author of a letter alleging that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her more than 30 years ago, the Palo Alto University professor’s life has been turned upside down. Beyond the international media attention and scrutiny by politicians trying to understand or explain away her account, Ford has fled her home, received death threats, and seen her email hacked, according to a letter her attorneys sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee.

By Monday, Ford had been doxed, thanks in part to Twitter users who repeatedly posted her personal information, including her address and phone number, and encouraged others to harass Ford and protest outside her home. Though Twitter appears to have taken some action to suspend at least one of the accounts behind this effort, as of Thursday afternoon, Ford’s personal information can still be found on Twitter, including information with her work email address and office location. At least one of the accounts that posted her personal information and campaigned to harass her, evidenced by multiple screenshots and complaint tweets to the company’s support account, is still active. Her personal information is also still available in deleted tweets and a deleted Reddit post that are searchable in Google’s cache.

The posting of someone’s personal information online in order to harass, harm, or intimidate is a time-tested tactic of online abuse, and it works. It’s been happening for well over a decade, which is why it’s so surprising that Twitter appears to struggle to protect obvious targets. Twitter did not immediately respond Thursday afternoon to the question of why Ford’s personal information appears to still be circulating on its platform.

The phone number and home address that are still being tweeted are the same ones that were posted on 4chan and 8chan—two message boards inhabited by trolls—at the start of the week. I found them on Twitter within 15 minutes of searching. Combating decentralized harassment campaigns may be like playing whack-a-mole, but there is, in theory, one easy solution to the problem: Block any tweets containing the numbers and addresses of victims. Twitter hasn’t done that. Nor has the company’s blocking of specific accounts done the trick, either. One of the most animated trolls dedicated to posting Ford’s information was suspended for 12 hours starting Sunday, as HuffPost reports, but returned Monday to continue tweeting out the professor’s personal details, though the user appears to be suspended now.

Twitter’s paltry actions are particularly vexing considering how predictable this mess is. The infamous neo-Nazi Andrew Auernheimer, known online as Weev, doxed tech blogger Kathy Sierra in 2007, posting her Social Security number and home address, and urged others to harass her, forcing her to flee her home. In 2013, the Washington Post published a story about a man who posted a sex ad online posing as his ex-wife that read, “Rape Me and My Daughters.” Fifty men reportedly showed up at their door. During the Gamergate controversy, multiple women were “swatted,” slang for when harassers who coordinate online place false calls to the police with the home address of their target or their target’s family, causing officers to arrive at their home armed, often in SWAT gear. Even law enforcement does it—as police in Berkeley, California, did in August when they posted the names and photos of more than a dozen anti-fascist counter protesters and activists before any charges were formerly filed, making it easy for far-right trolls to find them or for their employers to learn of their arrest.*

In this case, there’s even been some counterdoxing. After Ford’s information was shared, some of her supporters tried to dox one of the people who appears to have originally posted her personal information. Based on the photo and the name on the account in questions, Twitter users found someone with a similar photo and the same name who is the pastor of a small church in Philadelphia and appeared to be attempting to locate him, tweeting out photos of the church and his LinkedIn profile. I contacted the church to ask if its pastor is the same person who has been suspended from Twitter but have not heard back. But it does not appear that the counterdoxers attempted to verify his connection to Ford’s harassment before they began trying to find him.

While men tied up in political dramas get doxed, too, the tactic is most notoriously, and it seems most frequently, used to silence and harass women, as it was during Gamergate. And the horror of it all—random people showing up at your home, attempting to purchase things in your name, trying to steal your identity, threatening to kill or rape you, calling your personal cellphone, and worse—has a chilling effect on victims who would like to find justice. When this is what you get, of course many of them would be hesitant to speak up. When personal information ripples through a mainstream platform like Twitter, it makes all of this harassment far, far easier. So far, Twitter hasn’t shown it’s very interested in stopping it.

Update, 6:37 p.m.: Twitter says it has now taken down the tweets that Slate found this afternoon containing Ford’s home address, but stressed that tweets with information on her office location and email are not a violation of the company’s policy, because that information is publicly available on her university’s website. Twitter said the company is proactively working to find tweets that may break its rules in the case of Ford, but wouldn’t detail how or what it is doing to keep her personal information offline. A spokesperson added that the company takes the posting of personal information very seriously.

Correction, Sept. 20, 2018: This piece originally misstated the month when police from Berkeley, California, posted the names of arrested anti-fascist activists on Twitter. This was reported to have happened in August, not September.

Follow Us!