Why one of the world’s best fossil sites is full of severed bird feet

Speaking of Science

By Brian Switek WASHINGTON POST

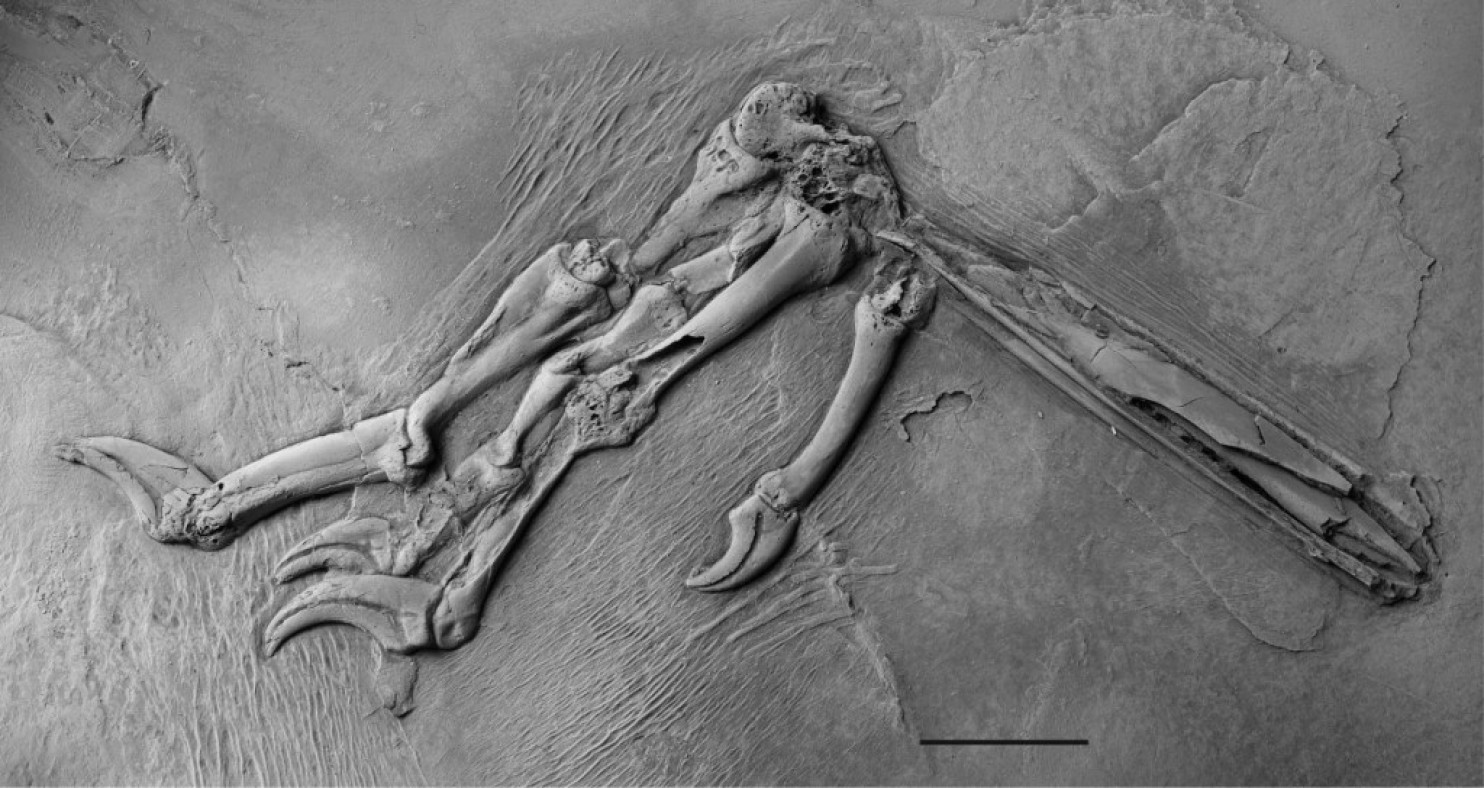

One of the isolated legs found in Germany. (Gerald Mayr)

Prehistoric creatures aren’t exactly renowned for their table manners. Most dinosaurs, for example, were incapable of chewing and had to swallow their food whole. But some ancient eaters were messier than others. And in southwestern Germany, something especially sloppy left severed bird feet strewn about a dense fossil boneyard.

The Messel Pit is one of the greatest fossil sites in the world. Within stacks of 47-million-year-old oil shale is an unmatched record of life in and around an ancient lake. There are early mammals preserved down to their fur, pairs of turtles that somehow died in the middle of mating, dozens of plant species and more than 1,000 bird skeletons. It’s the closest paleontologists can get to actually walking through a humid Eocene forest.

[Terrifying ancient crocodile discovered in the Sahara was almost the size of a bus]

Not all the Messel fossils are so dazzlingly complete, though. At least eight isolated bird feet have been pulled from the same stone. They were a curiosity, but mostly overlooked as experts focused on studying and describing birds that were more intact. But now Natural History Museum paleontologist Gerald Mayr has taken another look at the feet and come up with an explanation for how they became violently separated from the rest of the avians they once belonged to.

At many fossil sites, an isolated foot wouldn’t be much of a mystery. Bodies fall apart after death, and it’s rare to find intact and articulated body parts, much less whole skeletons. But the preservation at Messel is so delicate that the severed bird feet stood out, especially when Mayr found that they almost exclusively came from birds that lived on the shore and not on the lake itself. In a paper published in Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, Mayr suggests that crocodiles might be the answer to the quandary.

[Why scientists got an alligator to inhale helium]

A plethora of crocodiles haunted the Messel lakes. Up to seven species lived in this lush, wet place, and previous research identified a partial primate skeleton that was once a crocodile’s meal. The bird legs bear the signs of a deadly dinner party: All but one of the isolated legs were found to be fractured and missing pieces — similar to another bird leg found at different locality alongside a crocodile tooth, definitively putting a reptile at the scene of the crime.

A foot from another site, preserved with an incriminating tooth. (Gerald Mayr)

Together, Mayr writes, these pieces of evidence make crocodiles the prime suspects.

So how were the ancient crocodiles catching and feeding on these birds? “Unfortunately, an unambiguous interpretation of these specimens is difficult,” Mayr said. It isn’t clear whether the birds were caught at the shoreline or were washed into the water and scavenged. Still, from the damage to the bones, “it seems that prey was first seized at one of the feet, which was then torn off the body due to either prey manipulation of the crocodilian, escape attempts of the victim if a living bird was attacked, or both,” Mayr said.

If the crocodiles were dragging helpless birds into the water, they may have given an unwitting assist to paleontologists. The isolated bird legs belonged to medium- to large-sized birds that haven’t been found elsewhere, Mayr noted, and this has boosted the fossil life list of those who study Messel’s birds. If the crocodiles were attacking birds that would have otherwise never made it into the lake, then they helped add an important part of the ancient habitat’s record. “However,” Mayr said, “if these birds were carcasses drifting on the lake surface, crocodiles may have actually done a disservice to paleontology in eating most of the animal and just sparing the feet.” Hunger comes before service to science.

Brian Switek is a freelance science writer and the author of My Beloved Brontosaurus. For more, read his Scientific American blog and follow him on Twitter or Instagram.

Read More:

‘It was a monster’: Hunters kill enormous 800-pound alligator that was feasting on farm cattle

For the first time, scientists explore the atmosphere of an Earth-sized exoplanet

Watch these leaping electric eels validate one of science history’s wackiest stories

The gruesome price birds in the Everglades pay for using alligators as bodyguards

Slow lorises may prefer the booziest nectar

Follow Us!