THE MOST INCARCERATED CITY IN THE MOST INCARCERATED STATE CONSIDERS EXPANDING NOTORIOUS JAIL

The sheriff wants to solve the jail’s mental health crisis by adding more beds.

A 15-year-old boy found dead in his cell, asphyxiated by his mattress cover. A suicidal 63-year-old man hanging from a showerhead. A 24-year-old who wrapped a telephone cord around his neck.

Awaiting trial at New Orleans’ jail has been likened to a “death sentence.” Now, the “most incarcerated city in the most incarcerated state in the most incarcerated country in the world” is considering spending millions of dollars to expand the troubled facility.

A federal judge set a deadline of Tuesday for the city to come up with a plan to house mentally ill inmates. Sheriff Marlin Gusman is pushing a proposal to construct a new building, with hundreds of new jail beds. The expansion would cost an estimated $97 million to build.

The city, which has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, has steadily reduced the number of people in jail over the past six years. But if the new beds get built, community organizers warn, they won’t stay empty for long.

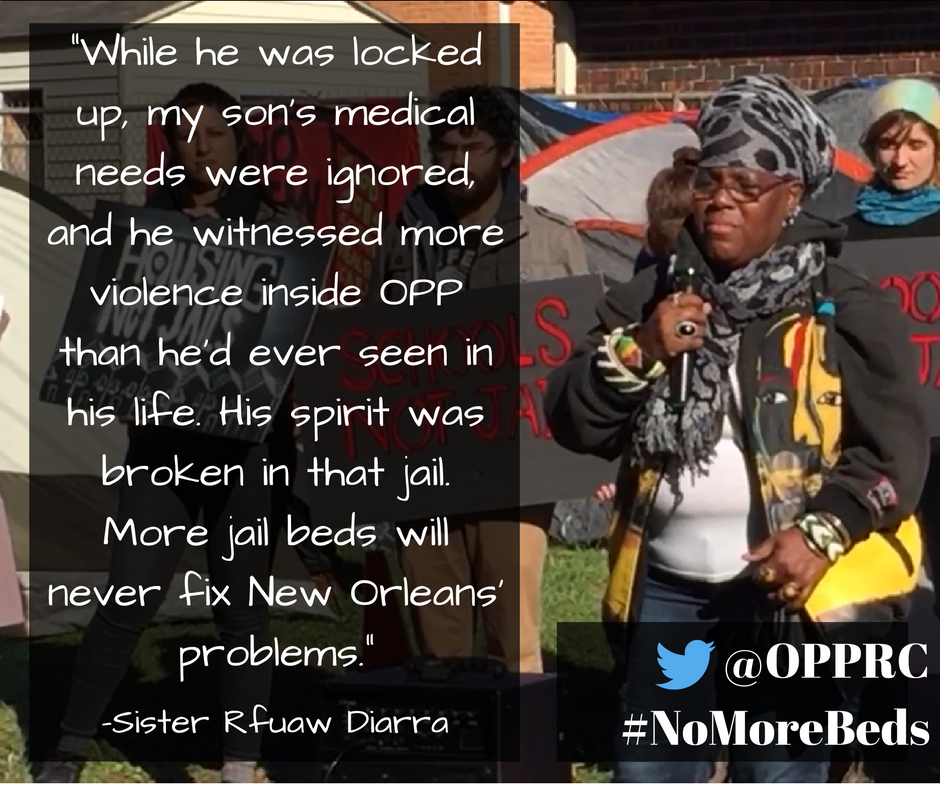

“As the incoming Trump administration takes power with its promises to be ‘tough on crime,’ we know that if those beds are built, they will be filled with our community members,” Alfred Marshall, an organizer who delivered a petition to city officials against the expansion, said in a press release.

Empty spaces

The current jail, which opened in 2015, has a curious layout. One building houses the intake processing center and jail cells. The second building houses the kitchen and warehouse. Between them is an empty plot of land. Stretching out to the empty space in the middle are two long gangways — the Orleans Parish Prison Reform Coalition (OPPRC), which is leading the anti-expansion campaign, calls them “bridges to nowhere.”

That empty lot makes clear that the sheriff always intended to expand the jail and build a third building later, OPPRC organizer Adina Marx-Arpadi said.

We know that if those beds are built, they will be filled with our community members.

The history of that empty space is fraught. Before Hurricane Katrina destroyed it in 2005, the decrepit Orleans Parish Prison housed 6,500 inmates on an average day, making New Orleans the most incarcerated city per capita. Federal funds after the storm presented an opportunity to shake that title and rebuild with a new vision.

The storm had decimated New Orleans’ population, so constructing a smaller jail made sense. Gusman originally proposed more than 5,000 beds in the new jail. But that plan would have given the city the capacity to incarcerate one out of every 60 residents remaining in the city.

The city council unanimously decided in 2011 to cap the jail at 1,438 beds, which still allows for an incarceration rate close to double the national average.

The sheriff, who was paid per prisoner until 2015, said that number was far too low to accommodate all the people who needed to be locked up. But he agreed to construct the new jail according to the city’s parameters — leaving open the possibility “to determine appropriate future facilities, if any are needed.”

Gusman opened the $150 million facility in September 2015, calling it “the beginning of a new day” that would shed the old jail’s reputation for violence and abuse.

But almost immediately after that rosy prediction, the horror stories started pouring in. Less than two months later, a man awaiting trial died after his chronic sickle cell disease went apparently ignored and untreated in jail. Soon after that, an inmate on suicide watch hanged himself in the shower. And last summer, a teenager allegedly killed himself after spending months awaiting trial.

It quickly became apparent that the sheriff had not designed the jail to accommodate mentally ill inmates, a requirement of the federal consent decree the jail has been operating under since 2013. A mental health expert testified that the conditions inside the jail were “abysmal.” Beyond barebones medical care provided by a private prison health care company, the jail lacked basic mental health services and psychiatric facilities.

“The issue is that the sheriff didn’t built those things to begin with, and so as a result he’s now asking for more beds and more space and millions of dollars more,” Marx-Arpadi told ThinkProgress.

Rather than build a whole new facility, OPPRC is calling for a retrofit of the current jail to accommodate mentally ill inmates. A panel of experts determined that renovating part of the jail would be the fastest and most cost-effective way to resolve the issue. The sheriff’s attorney dismissed their report as “propaganda.”

A costly undertaking

The efforts to improve jail conditions to meet basic constitutional standards have not gone smoothly. Independent monitors found the jail had gotten even worse because of the sheriff’s lack of leadership and indifference to the crisis. After mounting criticism, Gusman relinquished control of the jail to an independent monitor in October. Though the monitor now has final authority over the jail, the sheriff says he remains involved in these decisions.

Gusman has maintained for years that he cannot be held responsible for conditions within the jail because the city has not given him enough funding to address the problems. An attorney for the sheriff argued that outfitting the jail to provide mental health services are a “costly undertaking.”

But the violations are taking their own financial toll on the city. According to a recent analysis by the New Orleans Times-Picayune, the sheriff has been paying out massive sums of taxpayer money to lawyers and public relations firms who handle damage control after each new death in the jail. In 2015, he spent almost $2 million in legal fees over a slew of civil rights violations and wrongful death allegations.

Criminalizing mental health

Jails have become the primary mental health providers in the U.S. as states cut mental health services and criminalize behaviors like homelessness and drug addiction. In New Orleans, virtually no mental health safety net exists outside of incarceration.

Yet the city’s need for services is particularly dire after the trauma of Katrina. After the storm, the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and other serious mental illnesses skyrocketed, especially among poorer black communities that had lost the most in the chaos.

At the same time, the city lost much of its capacity to treat low-income people with mental illnesses. Former Gov. Bobby Jindal (R) made further cuts to safety net hospitals and state-run mental health services. As a result, police end up handling people better served by doctors.

“The only way, then, to access mental health care is by going to jail,” Marx-Arpadi said.

Though the construction of a new mental health building would be partly paid for by federal disaster funds, operating costs would still require millions of taxpayer dollars.

“If you’re building a building specifically for mental health care in the jail, the operating costs are going to be huge. And that’s money that’s not being put in those kinds of services in the community,” Marx-Arpadi said. “Spend the money you would spend building a mental health ward for the jail, and build it in the community.”

Keeping the community safe

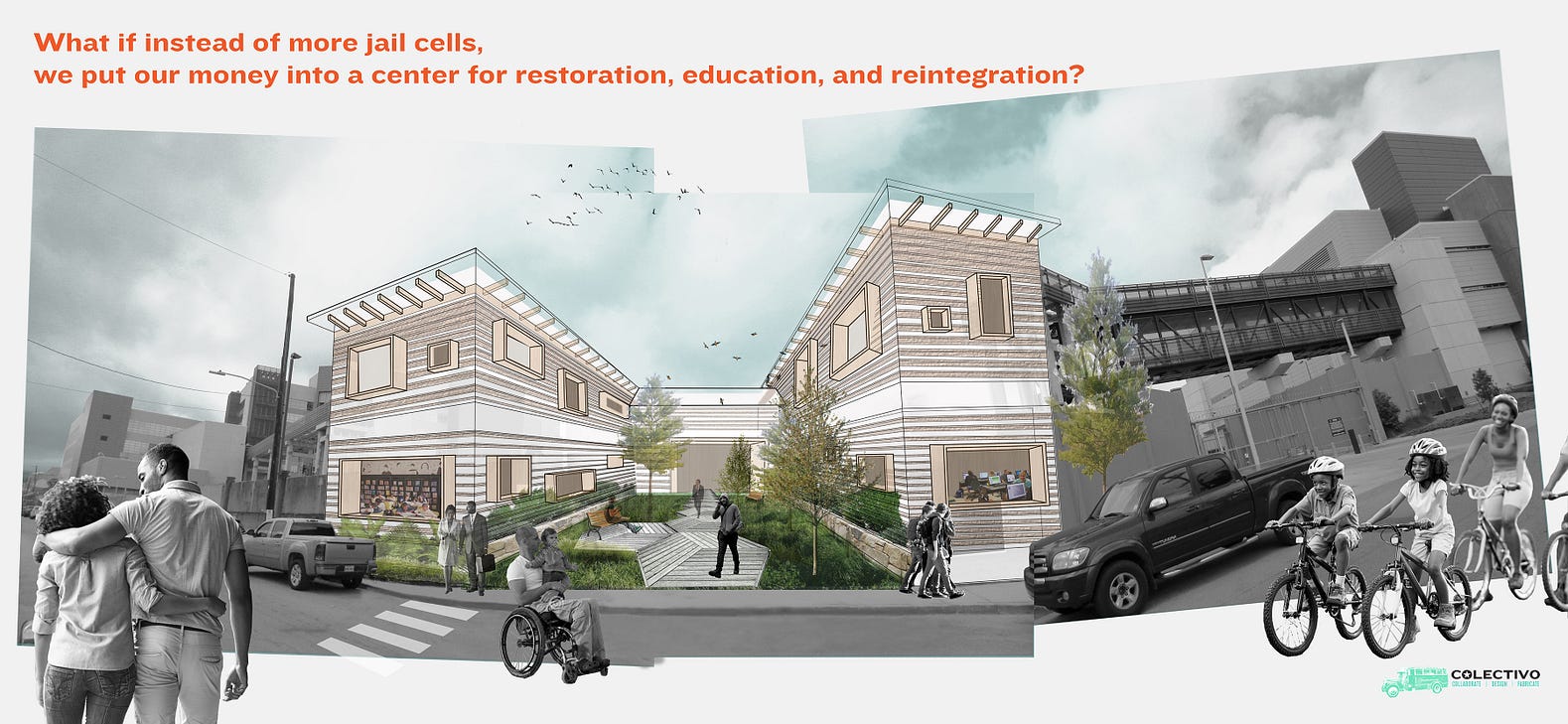

What happens to that empty lot in the jail complex if it’s not filled with more jail beds? Residents have some ideas.

Based on a community meeting they held to discuss the empty land, OPPRC has dreamed up a community center that could be constructed in that space instead.

Community members came up with a long list of ideas for such a center that they believe would better serve public safety than more jail beds. The facility could house a library for inmates, substance abuse counseling and re-entry programs, adult education classes — even a vegetable garden to help inmates process their trauma.

It could be years before city lawmakers are willing to seriously consider such a wishlist. But the brainstorming is intended to redefine what it means to “keep the community safe.”

“Any dollar you put into the jail is money you’re not spending in the community,” Marx-Arpadi pointed out.

Aviva Shen, a former ThinkProgress editor, is now a freelance writer in New Orleans focused on criminal justice.

Follow Us!